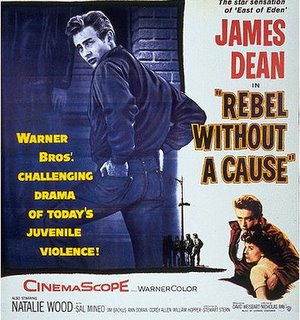

Rebel Without a Cause

Much like James Cagney, James Dean was another Hollywood star who wasted no time toiling away in bit parts. At the ripe old age of 24, Dean acheived cinematic immortality in only his second major role (his first was the role which put him on the map, the charismatic lead in Elia Kazan's "East of Eden" earlier that year). In actuality, immortality came a few weeks before his role was ever seen. Weeks before audiences would forever remember Dean and his fire engine red jacket in "Rebel Without a Cause", Dean was killed in a car accident. This tragic death turned Dean into a cult obsession, first among girls, and then years later as rumors of his personal life surfaced, amongst gay culture. His life certainly was interesting, albeit extremely and unfortunately brief, and a microcosm of that is his brooding portrayal of Jim Stark in Nicholas Ray's seminal examination of teenage-dom "Rebel Without a Cause". In addition to James Dean, Ray assembled an impressive cast of young actors, including Natalie Wood, who lobbied hard for the role of Judy, Sal Mineo, who gave an excellent portrayal of the tragic character Plato, and an impossibly young Dennis Hopper, as a gang member (rumor has it that Hopper's affair with Natalie Wood cost him Sal Mineo's larger role, thanks to director Ray's jealousy). For its time "Rebel Without a Cause" was an intense look at its difficult subject matter, and it holds up surprisingly well today, thanks mostly to Dean's incendiary performance, as well as the grim epilogue life administered for the film; in addition to Dean's premature death, both Sal Mineo and Natalie Wood also died young under tragic circumstances.

Much like James Cagney, James Dean was another Hollywood star who wasted no time toiling away in bit parts. At the ripe old age of 24, Dean acheived cinematic immortality in only his second major role (his first was the role which put him on the map, the charismatic lead in Elia Kazan's "East of Eden" earlier that year). In actuality, immortality came a few weeks before his role was ever seen. Weeks before audiences would forever remember Dean and his fire engine red jacket in "Rebel Without a Cause", Dean was killed in a car accident. This tragic death turned Dean into a cult obsession, first among girls, and then years later as rumors of his personal life surfaced, amongst gay culture. His life certainly was interesting, albeit extremely and unfortunately brief, and a microcosm of that is his brooding portrayal of Jim Stark in Nicholas Ray's seminal examination of teenage-dom "Rebel Without a Cause". In addition to James Dean, Ray assembled an impressive cast of young actors, including Natalie Wood, who lobbied hard for the role of Judy, Sal Mineo, who gave an excellent portrayal of the tragic character Plato, and an impossibly young Dennis Hopper, as a gang member (rumor has it that Hopper's affair with Natalie Wood cost him Sal Mineo's larger role, thanks to director Ray's jealousy). For its time "Rebel Without a Cause" was an intense look at its difficult subject matter, and it holds up surprisingly well today, thanks mostly to Dean's incendiary performance, as well as the grim epilogue life administered for the film; in addition to Dean's premature death, both Sal Mineo and Natalie Wood also died young under tragic circumstances.As the film begins, Jim Stark has been arrested for being drunk in public. The opening scene plays out in a series of long takes (which killed director Ray, who had to indulge his Method obsessed star by holding up shooting until Dean emerged from his trailer realistically drunk and enraged from wine and pounding Wagner music!) and it introduces us to both the three main characters as well as their relationships with their parents (or in Plato's case, parental guardians). Jim is taken home by his controlling mother and henpecked father, who means well but never stands up to his wife, a point which drives Jim crazy. Judy, who has run away, is taken home by her distant mother and hateful father, who refuses to show his daughter any affection, disgusted at the "slut" he thinks she has become. Plato, arrested for shooting squirrels with a bee bee gun, is in the most depressing of situations. Parents divorced, ostensibly living with his mother, who is always gone, Plato's only source of authority and parental guidance and affection is an overwhelmed maid/nanny, who means well but cannot possibly cope with the emotional problems plauging Plato. Jim is by nature a shy, introverted kid, but he is prone to violent outbursts, particularly when he feels the need to assert his father's authority for him, be it by standing up to his mother, or challenging the old man himself. Jim also allows himself to be goaded into a knife fight and a "chicken run", a deadly game of chicken involving driving cars towards a cliff, testing the other's nerves to see who bails out first. Jim's nemesis both times is Buzz, a hulking jerk, who happens to be Judy's boyfriend, if for no other reason than because she is so desperate for affection, she would rather subject herself to Buzz than attempt winning back her father's long forgotten love. After Buzz' accidental death in the chicken run, Judy is surprised to find warmth and kindess from Jim, who, while new to their high school, seems to understand Judy better than anyone else. Together with Plato, a pathetic figure ridiculed by kids his own age and ignored by adults, they form a bizarre trio, but establish a new age functional family unit, with Jim and Judy as mother and father, and Plato as their adoring son.

The new family's happiness is fleeting however. Buzz' gang comes after Jim, seeking revenge and end up chasing the trio to the Griffith Observatory (a stunning use of a real life Los Angeles landmark) where they hide out, at first from the gang, and then after Plato shoots one of the members, from the police. The ending is a tense standoff. Plato refuses to come out of the Observatory, and Jim bargains with the police to bring him out if there is no more violence. In the ultimate show of compassion Jim gives the frightened Plato his bright red jacket, an article of clothing Plato has cherished from the beginning of the movie, and which clearly touches his heart. As the two exit the Observatory, Plato gets frightened by the flood lights on him and tries to run, tragically prompting a volley of fire from the police. Jim and Judy are distraught, but together, the two leave the scene, arm in arm, no longer looking for, or expecting understanding and affection from their parents. This ending, of Jim and Judy seemingly striking off on their own, set the country's teenage hearts on fire. Between this and Marlon Brando's "The Wild One" from the year before, which ellicited the classic exchange "What are you rebelling against?", "Whaddya got?", teenagers began to feel as if they were being included. These films spoke directly to them, and not surprisingly, the number of teen oriented "message" movies spiked in the late 1950's with films such as "The Blackboard Jungle" which went a step further, incorporating a new teen craze: rock and roll music. For its mark on Hollywood, inspiring an entire new demographic's worth of films, as well as unfortunately being the brightest the James Dean star would ever burn on film, "Rebel Without a Cause" is a true classic.