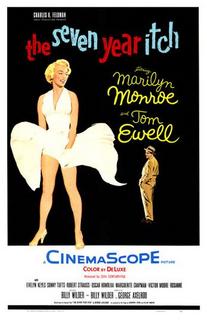

The Seven Year Itch

Most people do not know the name of the movie featuring the famous scene of Marilyn Monroe holding her skirt down as it is blown upwards while standing over a subway grate. That image is so ingrained in American pop culture however, a mere photo of it is a personification of Monroe's legendary sex symbol status, that the fact that the movie itself is largely forgotten is unfortunate. I remember having the same reaction to "Singin' in the Rain" when I first saw it. I was already familiar with the classic dance number, situated almost exactly at the film's halfway point, yet knew nothing about the film itself. My knowledge of "The Seven Year Itch" was even less impressive, making my reaction upon actually seeing the film that much more surprising. Whereas with "Singin' in the Rain" I could have crudely fashioned together some type of description, for instance, I knew that it starred Gene Kelly, Donald O'Connor and Debbie Reynolds, was obviously a musical and that at some point Kelly's character is so happy he "sings in the rain". My knowledge of "The Seven Year Itch" was confined to my awareness of that single scene, I did not even have any context for it. Her skirt blows up, a nation is entranced. I could not tell you the name of her co-stars, the film's director, the year of its release, or whether or not her skirt blowing up had anything to do with the plot. Luckily for me, I finally watched "The Seven Year Itch" one day, and found out all about it.

Most people do not know the name of the movie featuring the famous scene of Marilyn Monroe holding her skirt down as it is blown upwards while standing over a subway grate. That image is so ingrained in American pop culture however, a mere photo of it is a personification of Monroe's legendary sex symbol status, that the fact that the movie itself is largely forgotten is unfortunate. I remember having the same reaction to "Singin' in the Rain" when I first saw it. I was already familiar with the classic dance number, situated almost exactly at the film's halfway point, yet knew nothing about the film itself. My knowledge of "The Seven Year Itch" was even less impressive, making my reaction upon actually seeing the film that much more surprising. Whereas with "Singin' in the Rain" I could have crudely fashioned together some type of description, for instance, I knew that it starred Gene Kelly, Donald O'Connor and Debbie Reynolds, was obviously a musical and that at some point Kelly's character is so happy he "sings in the rain". My knowledge of "The Seven Year Itch" was confined to my awareness of that single scene, I did not even have any context for it. Her skirt blows up, a nation is entranced. I could not tell you the name of her co-stars, the film's director, the year of its release, or whether or not her skirt blowing up had anything to do with the plot. Luckily for me, I finally watched "The Seven Year Itch" one day, and found out all about it.Imagine my surprise when I discovered that this film was directed by Billy Wilder. Suddenly I had expectations for this film I knew next to nothing about. Billy Wilder, while widely recognized as a great comedy writer in his time, should today be given even more credit for being one of the greatest comedy writers of all time. His brazen scripts often pushed the envelope in terms of what was socially acceptable to make fun of, and he was making sex comedies long before Woody Allen was, they were just neutered by the Puritanical Hays Code, which governed Hollywood for far too long. Wilder's genius, and clever manipulation of the stuffy Hays Code, is refreshingly and readily apparent from the film's first frames. The titular itch we find is a clinical term for the doubt a married man begins to have about whether or not the sanctity of his marriage is more important than satisfying his primal physical wants and has been bothering husbands of Manhattan since the days when the Indians were sending their wives "up river", only to immediately be tempted by a passing beautiful woman. This scene is then repeated shot for shot, with I believe the same actors, in New York's Grand Central Station, proving that the itch is timeless and universal. It is amidst the mobs of people in Grand Central where we first meet Richard Sherman, who is packing his wife and son off to go "up river" for the summer. The city is sweltering and Richard is busy with his book publishing job, but neither issue will bother him as much as his new upstairs neighbor, the blonde bombshell who goes nameless, but who we know as Marilyn Monroe.

Richard is immediately smitten with The Girl, (how she is officially credited) and invites her over for drinks. Almost instantly he begins to have paranoid daydreams about the extent to which he is cheating on his wife, and about her somehow finding out about what he is doing with the gorgeous younger woman in their apartment. Of course, nothing happens between the two of them, and this is where Billy Wilder's comedic expertise is invaluable. Billy Wilder milks "nothing" happening between his two leads for all its worth, creating elaborate scenarios in which Richard's paranoia and neuroses are mined for laughs, fifteen years before Woody Allen became famous for making fun these same very things. The similarities between Wilder's work here and Allen's work to come are unmistakable. The Manhattan setting, the everyday guy inexplicably linked to a beautiful woman, the audience having constant, and often times hilarious insight into his male protagonist's thoughts and feelings. The funny thing is that all along, while Richard becomes more and more concerned that his wife is going to find out he is involved in all this duplicity and intrigue, the more obvious it becomes that The Girl has no intention of doing anything with Richard. She likes him well enough, and they do spend some of their evenings together, but she knows their relationship for what it is, being a beautiful woman she has many of them, a harmless married man who cannot help but fawn over her. Eventually Richard realizes this, around the time his wife and son are due back from New England, and The Girl is moving on, only in the city for the summer, to seemingly tempt Richard and pitch tooth paste on the radio. Before she leaves, however, she finds time to pause over a subway grate, thus giving birth to one of the most iconic images of classical Hollywood cinema. The rest of the movie is pretty great too though.